Diferencia entre revisiones de «Autores/ENG»

< Autores

(Página creada con «__NOEDITSECTION__ <br /> <div class="row"> <div class="small-12 small-centered columns"> <div style="float: right; margin-left: 20px;">__TOC__</div><br /> <poem>''Goodbye...») |

(Sin diferencias)

|

Revisión del 08:06 19 jul 2022

Contenido

Goodbye, poets, writers

as my sheets wrote

as much as little stories

comedies, and other notes.

(Aquí está la calavera, by popular publisher A. Vanegas Arroyo, 1902)

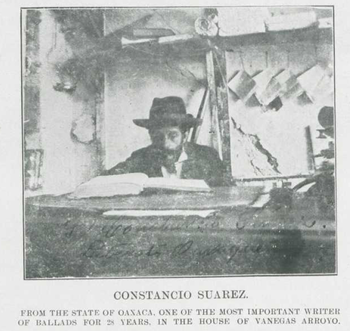

These “popular mockingbirds” are, however, elusive figures, whose names not always feature clearly on the prints. Because of this, the details of instances in which their names are clearly mentioned are enormously interesting. The broadsides and booklets published by Antonio Vanegas Arroyo in Mexico by the late 19th and early 20th century do not often name their authors. It is highly possible that most writers would not be keen on building their literary career on this —at least from a highbrow perspective— disreputable publishing house. But a couple of authors did sign their texts with pride:

Don Antonio used to accept all kind of things. Some were good, written by real authors who chose to “opt out” and did not sign their texts. Others, on the contrary, even gave him the original, as long as they were able to see their names and surnames printed under their heartfelt dirges. In exchange they received a number of copies, which they would show off and give to their acquaintances.[2]

Engraving, possibly representing Arturo Espinosa, printed on broadsheet, with auto-referential verses signed by himself. (¡Basta ya!, 1910).

The practice of authorial declaration would not change radically until around the third decade of the 20th century. This can be identified in the songbooks published by Eduardo Guerrero and Antonio Reyes in Mexico, and in Spanish broadsheets from various printing houses. These changes are partly due to the context of cultural production and consumption of the time, which propitiated the dialogue between printed popular literature and other emerging media and “cultural industry” phenomena, such as record labels and cinema.[3] As pointed out by Vicente T. Mendoza, this had an impact on the development of genres like the corrido, which was, subsequently, studied in relation to a specific cultural region by Guillermo Bonfil Batalla.[4] Bonfil Batalla notes that:

[…] we found real printed collections signed by their authors, among which were names such as Refugio Montes, Federico Becerra, Fausto Ramírez, Samuel Lozano, Juan Montes, and many more, who, even if they are not the authors of the most typical corridos (lyrics and music), have nevertheless greatly contributed to the shaping of the collections which are now printed.[5]

Inventory

Referencias

- ↑ See Pedro Cátedra, Invención, difusión y recepción de la literatura popular impresa (siglo XVI), Mérida, Editora Regional de Extremadura, 2002.

- ↑ Arturo Espinosa, [Biografía de Antonio Vanegas Arroyo], unpublished manuscript, Mexico, 1952, f. 8. (Colección Chávez-Cedeño).

- ↑ See Tomás Cornejo, “Fábricas de cultura popular. Consideraciones sobre la circulación de cancioneros impresos desde Santiago de Chile a Ciudad de México (1880-1920)”, Trashumante. Revista Americana de Historia Social, no. 15, 2020, p. 22.

- ↑ See Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, “Trovas y trovadores de la región Amecameca-Cuautla” in Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, Teresa Rojas Rabiela and Ricardo Pérez Montfort, Corridos, trovas y bolas de la región de Amecameca-Cuautla. Colección de don Miguelito Salomón, Mexico, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2018, pp. 11-32.

- ↑ Vicente T. Mendoza, El romance español y el corrido mexicano. Estudio comparativo, Mexico, Ediciones de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma, 1939, p. 145.

|

|